The popular understanding of the overwintering behaviour of honeybees should be reconsidered, according to a researcher.

Derek Mitchell from the University of Leeds investigated the clustering habit of the pollinators to find that it could be a distress action rather than a reaction to decreasing temperatures.

The researcher from the university’s Institute of Thermofluids said: “Honeybees in manmade hives may have been suffering the cold unnecessarily for over a century because commercial hive designs are based on erroneous science.”

Derek explained that the assumption that colonies’ dense gathering in the cold period provided them with insulation had been essential to apiculture for more than a century.

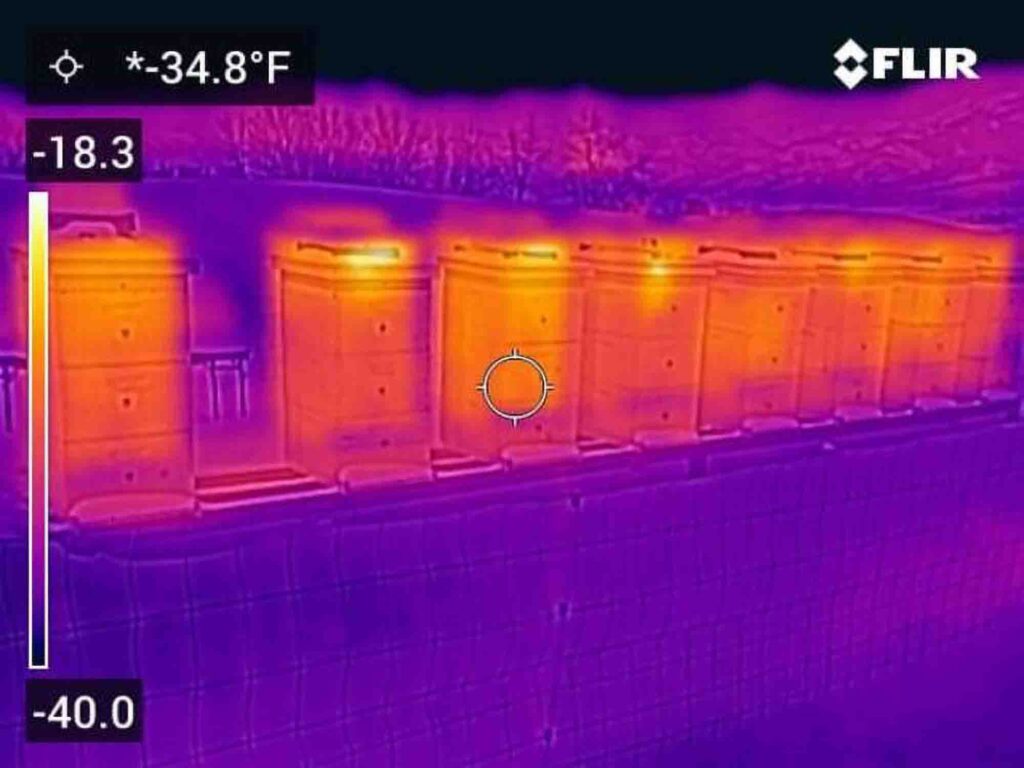

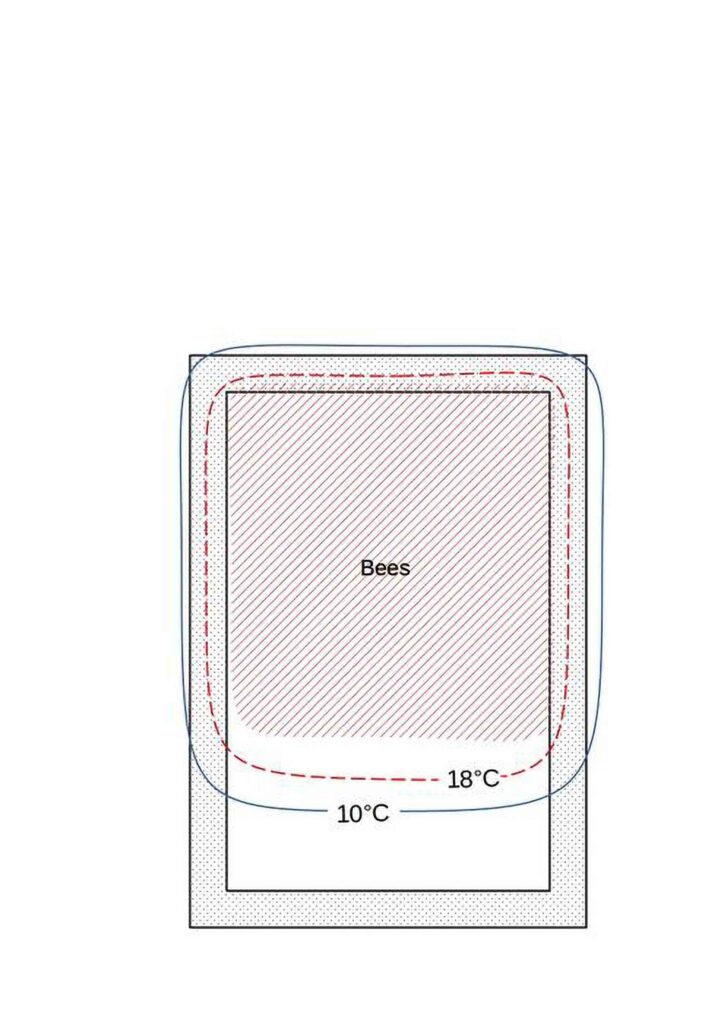

He told The Conversation: “Honeybee colonies don’t hibernate. In the wild, they overwinter in tree cavities that keep at least some of their numbers above 18 degrees centigrade in a wide range of climates, including minus 40 degrees centigrade winters.”

The researcher said that the common understanding of their wintertime traits was dominated by observing what happened in the thin manmade hives.

Derek emphasised: “These hives have very different thermal properties compared with their natural habitat of thick-walled tree hollows.”

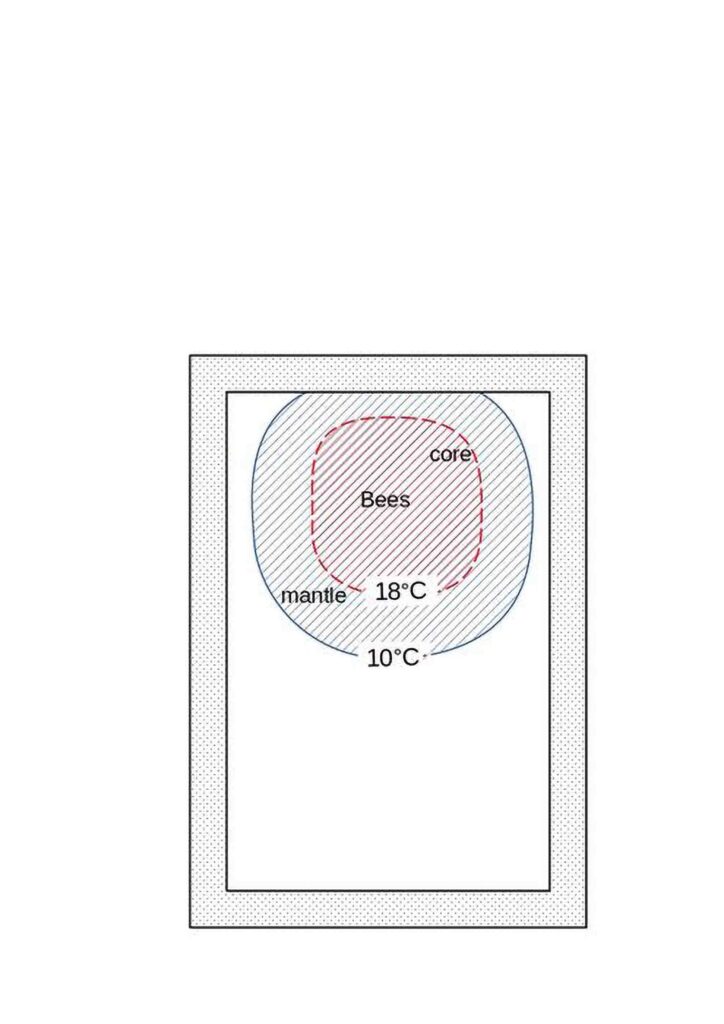

The scientist added: “Since 1914, beekeeping texts and academic papers have said the mantle ‘insulates’ the inner core of the hive. This meant beekeepers saw clustering as natural or even necessary.”

Derek said his study determined that cluster mantles were, in fact, working like a “heatsink” which decreased insulation.

He argued: “Clustering is not a wrapping of a thick blanket to keep warm but more like a desperate struggle to crowd closer to the ‘fire’ or die. The only upside is that the mantle helps keep the bees near the outside alive.”

Derek added: “Heat will always try to move from a warmer region to a colder one. The rate of heat flow from the core bees to the mantle bees increases, keeping those bees on the outside of the mantle hopefully at 10 degrees centigrade.”

According to the researcher, scientists and apiarists failed to consider the part played by the air gap between the hive and the cluster.

Derek said: “The thin wooden walls of commercial hives act as little more than a boundary between the air gap and the outside world. We urgently need to change the beekeeping practice to reduce the frequency and duration of clustering.”

He admitted that his findings were “controversial” and said he wanted to “raise awareness” and help to “educate” beekeepers.