The reason honeybees are dying out may be genetic and not related to the environment or disease, according to new research.

If correct, it offers hope that gene research could reverse the trend that has seen the lifespan of bees shrink dramatically since the 1970s.

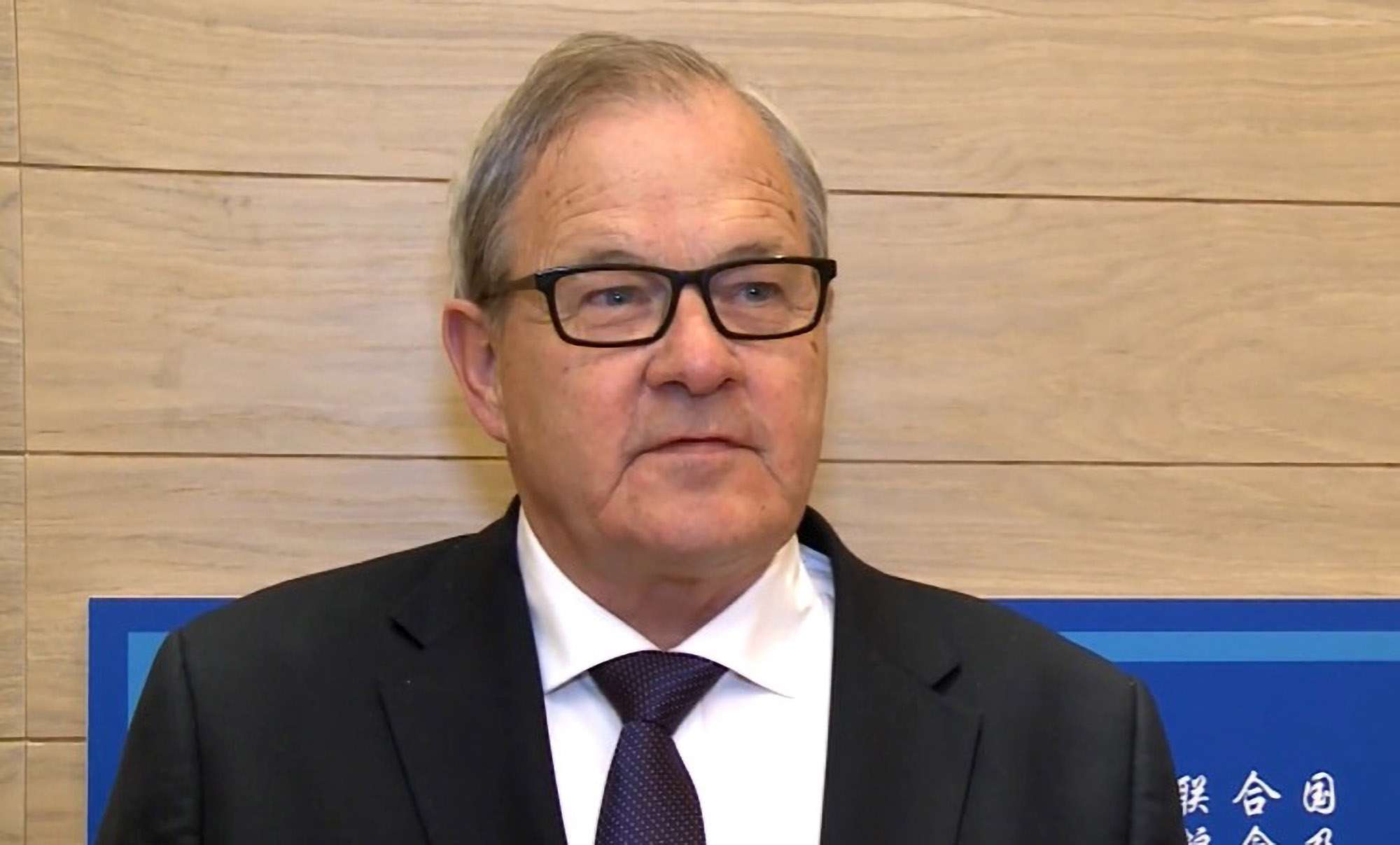

The investigation by Dr Dennis VanEngelsdorp and Anthony Nearman – which is the first study to show an overall decline in honeybee longevity potentially independent of environmental stressors – suggests that genetics may play a greater role than previously expected.

The entomologists from the Honey Bee Lab at the University of Maryland (UMD) in College Park, Maryland, think that the decline could help explain the loss of colonies and low honey production as experienced across the world in the past few decades.

Domesticated honeybee colonies naturally die and get replaced by apiarists. However, beekeepers in the United States and elsewhere observed exceptionally high losses within the last 15 years.

Previous studies into the matter by experts at different higher education institutions have put the focus on diseases, parasites and the application of insecticides.

Mr Nearman – who is an expert on honeybee pathophysiology – said: “We’re isolating bees from the colony life just before they emerge as adults, so whatever is reducing their lifespan is happening before that point.”

The PhD student and study lead author explained: “This introduces the idea of a genetic component. If this hypothesis is right, it also points to a possible solution. If we can isolate some genetic factors, then maybe we can breed for longer-lived honeybees.”

The UMD Department of Entomology researcher first noticed the lifespan decrease when while examining standardised lab protocols for rearing adult bees.

To replicate previous research activities, Mr Nearman and Dr VanEngelsdorp collected bee pupae from hives when they were within 24 hours of emerging from their wax cells. The collected insects grew in an incubator before being kept as adults in cages.

As Mr Nearman tried to determine the effect of supplementing the caged bees’ sugar water diet with plain water, he realised that their lifespan was around 50 per cent of the longevity of bees kept in similar lab experiments in the 1970s.

Reflecting on his experiences, Mr Nearman said: “When I plotted the lifespans over time, I realised that there actually is this huge time effect.

“Standardised protocols for rearing honeybees in the lab weren’t really formalised until the 2000s, so you would think that lifespans would be longer or unchanged because we’re getting better at this. Instead, we saw a doubling of mortality rate.”

Laboratory circumstances are significantly different than the environment in an outdoor honeybee hive. However, data on the social insects studied in labs suggest a similar lifespan compared to colony bees.

When the UMD team modelled the effect of a 50 per cent reduction in lifespan on a beekeeping operation, the resulting loss rates were ranging around 33 per cent. This rate is similar to the average overwinter and annual loss rates of 30 to 40 per cent as reported by North American apiarists in the past 14 years.

Mr Nearman and Dr vanEngelsdorp noticed that their lab-kept bees could be experiencing some sort of low-level viral contamination or pesticide exposure during their larval stage when they are brooding in the hive and worker bees are feeding them.

The bees have nevertheless shown any substantial symptoms of such kind of exposure. At the same time, a genetic component to longevity has been shown in other insects such as fruit flies.

The UMD entomologists – who published their study entitled “Water provisioning increases caged worker bee lifespan and caged worker bees are living half as long as observed 50 years ago” in the journal Scientific Reports – now plan to compare honeybee lifespan developments across the United States and in other countries.

The aim of the university’s Honey Bee Lab is to “bring a fresh perspective to solving problems.”

On its website, the institution says: “We are proud to share our research into the major mechanisms that are responsible for recurring high loss levels in honey bee populations, such as pests and pathogens associated with honey bees, loss of natural forage habitat due to large monocultural croplands, and pressure from human-induced changes in the environment.”