Researchers in the United Kingdom have used an insect version of the straight-line walking challenge to show for the first time that insecticides damage the nervous system of honeybees.

Neurologists have carried out such tests on humans to diagnose disorders caused by malfunctions of the parts of the brain that coordinate movement.

Now a team of scientists headed by Dr Rachel Parkinson – who is a post-doctoral researcher at the renowned University of Oxford – has taken a similar approach to determine the effect the application of so-called neonicotinoids is having on honeybees.

Dr Parkinson said: “Here we show that commonly used insecticides like sulfoxaflor and the neonicotinoid imidacloprid can profoundly impair the visually guided behaviour of honeybees.

“Our results are the reason for concern because the ability of bees to respond appropriately to visual information is crucial for their flight and navigation, and thus their survival.”

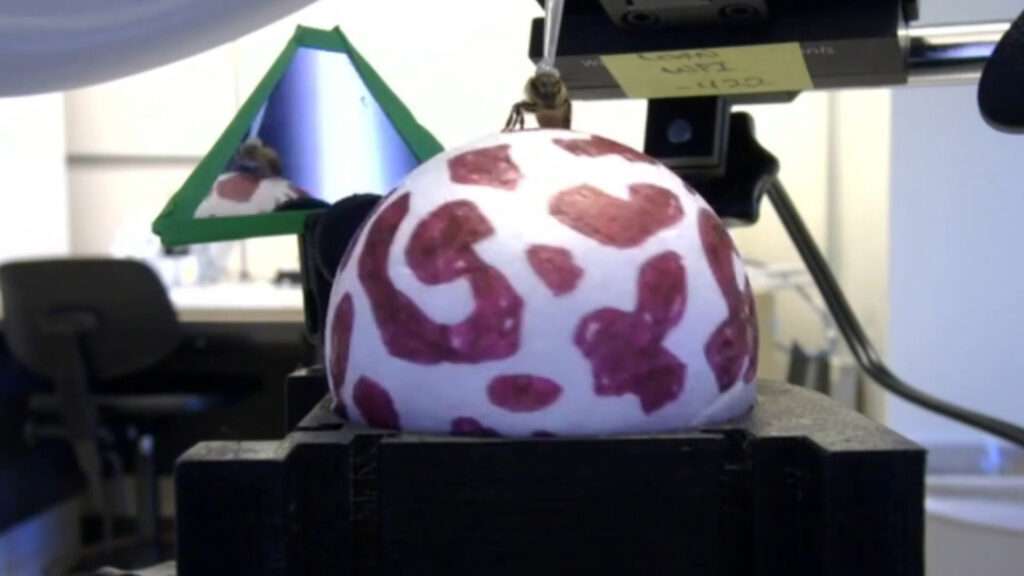

Insects’ so-called optomotor response allows them to orient themselves back onto a straight trajectory when they are at risk of steering off their track while walking or flying.

The Oxford University research group challenged the optomotor response of walking honey to respond accurately and timely to videos of vertical bars that moved from left to right, or vice versa, across two screens in front of them.

This setup tricks the social insects into assuming that they have suddenly been blown off-course and need to perform a corrective turn to return to a straight path.

A healthy optomotor response will navigate the motor system to orient back to an illusory straight line midway between the optic flow from the right and left.

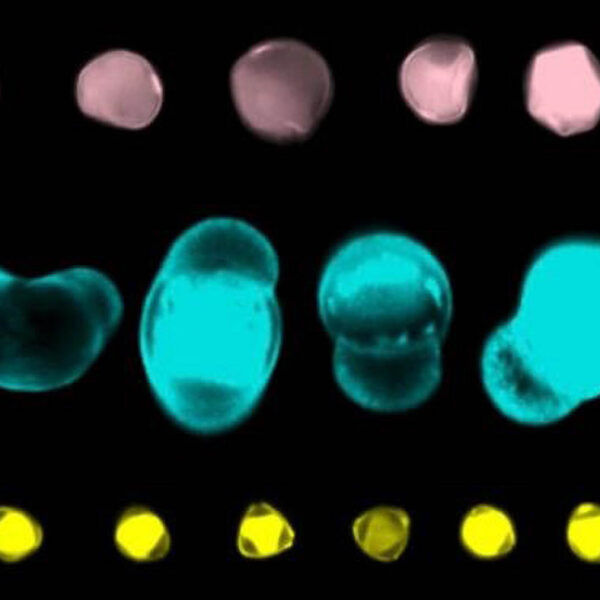

Dr Parkinson and her colleagues compared the efficiency of the optomotor response between four groups of wild-caught forager honeybees, with between 22 and 28 bees tested per group.

Each of them had been allowed to drink an unlimited amount of molar sucrose solution over five days, either pure or contaminated with imidacloprid and sulfoxaflor, two controversial pesticides.

All bees were less good at responding to the simulated optic flow when the bars were narrow or moving slower than when they were wide or moving fast.

However, the bees who had ingested the pesticides performed poorly compared to the control group. They turned quickly in just one direction or showed a lack of turning responses.

Overall, the asymmetry between left and right turns was at least 2.4 times greater for insecticide-exposed bees than for the insects of the control group.

Dr Parkinson explained: “Honeybees use wide-field visual motion information to calculate the distance they have flown from the hive. This information is communicated to conspecifics during the waggle dance.”

The neuroethologist warned: “Seed treatment insecticides, including neonicotinoids and novel insecticides like sulfoxaflor, display detrimental effects on wild and managed bees, even when present at sublethal quantities.”

According to Dr Parkinson, the application of these substances negatively affects the bees’ in-flight navigation and homing ability.

The study by Dr Parkinson and her co-authors entitled “Chronic exposure to insecticides impairs honeybee optomotor behaviour” has been published in the scientific magazine Frontiers in Insect Science.

Dr Parkinson concluded: “To fully understand the risk of these insecticides to bees, we need to explore whether the effects we observed in walking bees occur in freely flying bees as well.

“The major concern is that, if bees are unable to overcome any impairment while flying, there could be profound negative effects on their ability to forage, navigate, and pollinate wildflowers and crops.”

The United Nations (UN) warned that “widely divergent standards of production, use and protection from hazardous pesticides” in different countries were creating “double standards” which would have a serious impact on human rights.

The organisation called for a comprehensive new global treaty to regulate and phase out the use of such substances in farming and refocus on sustainable agricultural practices instead.

The UN underlined that constant exposure to pesticides had been linked to serious conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, hormone disruption and different kinds of cancer.

It emphasised that certain insecticides “can persist in the environment for decades and pose a threat to the entire ecological system on which food production depends.”

Regarding bees, the UN expressed concerns that the application of neonicotinoids could lead to a systematic collapse in the number of bees around the world. It concluded: “Such a collapse threatens the very basis of agriculture as 71 per cent of crop species are bee-pollinated.”